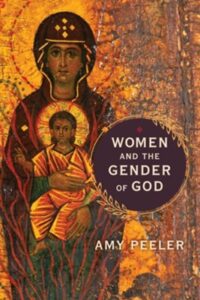

Amy Peeler, Women and the Gender of God (Eerdmans, October 2022), 286 pages. $24.99.

Years ago, the late Hollis Gause and Kimberly Alexander published Women in Leadership: A Pentecostal Perspective (2006). In conversations about that book, I’ve often said that its weakness is that it does not offer a serious consideration of the role of Mary, the mother of Jesus, as a paradigm for women in ministry. Amy Peeler has done just that.

Peeler, associate professor of New Testament at Wheaton College, writes from within an Evangelical tradition that takes Scripture and classical theology seriously. In so doing, she offers a work that seeks to be faithful to both, while challenging ways in which both have been read to give priority to a masculine hermeneutic of the Christian Faith. She also challenges the way radical feminists have misread Scripture and classical theology.

Peeler asserts, correctly in my view, that the Christian understanding of God has its foundation in the Incarnation. This requires a proper understanding of God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit; but also, a proper understanding of Mary’s role in the Incarnation and how she exalts the role of women in the mission of God.

In agreement with classical and orthodox Christian theologians, Peeler affirms that God is ungendered Spirit (neither male nor female) who nonetheless is revealed as Father. But God is Father in a way that is unique and different from human fathers. Whereas, human fathers contribute their essence (DNA) in the procreation of children, God has created humanity, and the cosmos, from nothing. Furthermore, God the Father eternally generates the Son and eternally spirates the Spirit in a way that is unique to the Holy Trinity. Even so, referring to God as Father is necessary to maintain the “undeniably personable” relations within Holy Trinity and between God and humanity (110). God cannot be properly called “Mother” because the Incarnate Christ has only one divine Father and one human mother. As Peeler declares, “Jesus does not call God ‘Mother’ because he already has one” (115).

Again, with classical and orthodox Christian theologians, Peeler affirms that Jesus Christ is the son of God and son of Mary who is the male savior of all humanity – but “a male who became embodied like no other” – virginal conception (121). Unlike all other humans who receive their “flesh” (DNA) from a father and mother, Jesus received his flesh from a single human parent – his mother. She writes, “To send the Savior, the Spirit came upon only one human, and that human was a woman” (136). Jesus is “a male embodied Savior with female-provided flesh” who saves all. Furthermore, the nature of the Incarnation precludes the possibility of a female Messiah. Peeler explains, “To be a human is to be born, born of a woman. The only way it is possible within the system of human procreation for God to involve both sexes in the revelation of divine embodiment is to have the image of God born as a male from the flesh of a female” (141).

Peeler concludes by lifting up the ministry of Mary as more than being the nurturing parent of God’s son. Mary is also a proclaimer of the gospel (153). The Incarnation is proof that God values women, that women are created in the image of God, and that women are called to function within church as teachers, preachers, and leaders.

Peeler’s work is significant in the development of a Protestant (and Pentecostal) appreciation for the role of Mary in the Incarnation, and as a paradigm for women in ministry. Furthermore, she challenges the masculine theology of ministry from those who traditionally venerate Mary as “Mother of God,” i.e., Roman Catholics and Orthodox. Those who insist that God is masculine and that Christian ministry is limited to men will find this work challenging. I found it to be profoundly helpful.

For my posts on the subject see here.