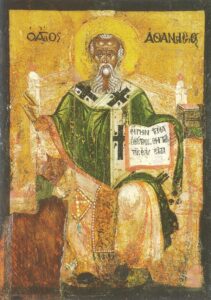

The third article of the Nicene Creed simply states, “We believe in the Holy Spirit.” Such a brief statement would lead one to believe that fourth century pneumatology was under-developed. However, Athanasius presents a well-developed theology of the Holy Spirit. His reputation as the champion of Nicene Trinitarianism is secured with his On the Incarnation of the Word and Letters to Bishop Serapion. Athanasius’ Trinitarian theology does not appear in a vacuum, but was developed to answer challenges to the apostolic tradition as stated in the Rule of Faith. The wide acceptance of Athanasius’ work by his contemporaries suggests that he articulated and clarified a received Trinitarian theology.

In the First Letter to Serapion, written after the Nicene Council, Athanasius answers challenges posed by theological opponents who deny the ontological status of the Holy Spirit as god.

First, Athanasius challenges the “mode of exegesis” of his opponents – the Pneumatomachi – those who fight against the Spirit. He presents a proper biblical exegesis that supports the deity of the Holy Spirit. He charges that those who deny the deity of the Holy Spirit follow the theological system of the Arians. Whereas the Arians declared that the Son was created by the Father; they likewise insist that the Holy Spirit is created by the Father and exists in a hierarchy of angels. This hermeneutic presents God as a compound being. To the contrary, Athanasius insists on the simplicity of God. This means that God is not a compound divine being, from which the Son and Spirit are parts. Rather, God’s being (ousia) is singular. Just as the Son is eternally begotten from the fullness of the Father; the Spirit eternally proceeds from the fullness of the Father. This does not represent a process, or change in the divine nature, for God is immutable. Therefore, the Son and the Spirit are consubstantial with the Father.

Second, Athanasius makes a clear distinction between the Son and the Spirit. The Holy Spirit “is named together with Christ” (and glorified together) but is “different and separated from the Son.” It is through the Spirit that the Father “through the Word perfects and renews all things.” The Holy Spirit is the “Power of the Most High” (Luke 1:35) and the “Spirit of Almighty God” (Zechariah 4:6). The Spirit proceeds from the Father, but is not another Son. The Word and Spirit are not brothers, nor is the Spirit a grandson of the Father. The Trinitarian relationships are not to be understood as analogous to human relationships. Nowhere in Scripture is the Holy Spirit called Son.

Third, Athanasius presents an explanation for the coinherence of the Father, Son, and Spirit. The names Father, Son, and Spirit are stable and signify distinct relationships within the immutable Holy Trinity. The Trinity is consubstantial, “indivisible and self-consistent.” The Son is begotten of the Father, the Spirit proceeds from the Father and is “given and sent” from the Son. The Spirit possesses the immutability of the Father and Son and is “the image of the Word and proper to the Father” in substance. To see the Son is to see the Father; likewise, to have the Spirit is to have the Son. The Spirit is not external to the Son, nor is the Son and Spirit external to the Father.

Finally, Athanasius presents an explanation of the Trinitarian faith as expressed in the Baptismal confession of Matthew 28:19. It is through the divine Holy Spirit that humans participate in the life of God. The Father creates and renews all things (i.e. divinization) through the Word in the Holy Spirit. The gifts of the Spirit are bestowed by the Father through the Word. The Father, Son, and Spirit are perfect in holiness and unity, self-consistent, indivisible, with a singular will and activity. The Trinity is not a linguistic expression (i.e. modalism), but represents actual divine ontology. Anything less invalidates Baptism. The baptismal confession cannot be divided among the divine names. According to Athanasius, to be baptized in the name of the Son to the exclusion of the Father and Spirit (i.e. Oneness Pentecostalism), or to deny the deity of the Spirit, seeks to divide the indivisible God and makes baptism an empty rite. Such a person is “worse than an unbeliever.”

Athanasius’ dogmatism seems somewhat unreasonable to a postmodern mind that values heterodoxy over orthodoxy. Even so, he insists that those who reject Nicene Trinitarianism are not worthy of the name Christian. By rejecting the full deity and distinctiveness of the Son and Spirit, his opponents have forsaken the Faith and fallen from grace (cf. Galatians 5:4). According to Athanasius, the proper confession and understanding of God as Holy Trinity is essential to salvation (cf. Matthew 28:19). To deny the Scriptural teaching of the Holy Trinity is to deny the truth of the Faith.

*Athanasius and Didymus the Blind, Works on the Spirit. Popular Patristics Series. Saint Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2011.